(Editor’s note this is part of a piece from “Exponential Causality,” which Jimmy Dunne is working. You can read Dunne’s work on his substack click here. )

By JIMMY DUNNE

The smolder no one killed, and the sheep who watched it roar.

This is a story about how micro-events—micro choices—inside city departments and fire agencies, turned a smoldering hillside that should have been extinguished into one of the worst wildfire disasters our nation has ever experienced.

On January 1, 2025, embers from the Lachman Lane blaze smoldered— and very likely reignited under fierce Santa Ana winds on January 7. It sparked the Palisades Fire that burned about 23,448 acres, destroyed more than 6,800 structures, and killed 12 people. Financial impacts to homeowners, to businesses, and to employees are unparalleled.

Let’s start six days earlier.

January 1, 2025. A small vegetation fire, five to eight acres, on Lachman Lane in the Palisades Highlands. An arsonist has been identified and is standing trial. Fire crews knocked it down fast. It was contained by morning.

Everyone goes home.

But the next day, January 2, firefighters on patrol text their battalion chief: deep hot spots still glowing in the duff, smoke curling from root channels.

Standard wildfire science: smoldering combustion can live underground for days, even weeks, breathing through tiny fissures, waiting for oxygen. One good gust and it’s a blowtorch.

The texts are real. So are the warnings.

The order comes back: “Stand down. No extra crews. The fire is contained.”

Paperwork closed.

The January 7 Palisades Fire was a holdover fire from the January 1 Lachman Fire. that was allegedly extinguished the week before.

Micro-choice #1.

No one digs ten feet down to drown the roots. No one assigns a patrol for the week.

Budget lines, staffing shortages, the holiday skeleton crew—whatever the reason, the ember is left alive.

For six quiet days it waits, patient as cancer.

Then January 7 arrives. Santa Ana winds beginning to gust—air so dry it sucks moisture from living wood. One breath of that wind finds the ember. Oxygen rushes in.

Heat that had been sleeping at 300 °F—spikes to 1,500 °F in seconds.

A single tongue of flame climbs a blade of grass. Then a shrub. Then it crowns into coastal chaparral that hasn’t burned in seventy years.

From there, the math is merciless.

In high winds, with aligned fuels, a wildfire doubles every fifteen to thirty minutes in the early hours. One acre becomes two, four, eight, sixteen—23,448 acres in days. Spot fires hurl embers a mile ahead, starting new fronts before anyone can reach them.

Every house that burned, every life lost, every child who will never be conceived because a parent died that week—every single one traces back to the moment someone decided a glowing root was “good enough.”

But the story of Exponential Causality in the Palisades Fire isn’t only about physics and the spark.

It’s also about the hundreds of engines and significant firefighters who showed up—and then sat.

For three straight days and nights, a huge percentage of the strike teams were ordered to stage in the parking lots at Will Rogers State Beach and Temescal Canyon. Firetrucks nose-to-tail under the streetlights. Crews in full turnout gear, sitting on tailgates, waiting for assignments that never came fast enough.

Residents reported that numerous firetrucks were parked at Paul Revere Middle School and in the Will Rogers State Beach parking lot while the fire raged on November 7 and 8.

While they waited, spot fires—no bigger than campfires—landed in backyards half a mile away. Micro-flames lick eaves, igniting a single bush next to a house.

Ten minutes with a hose line, two firefighters, and that house is saved. Ten more minutes, and the whole block feeds the monster.

But orders were, “Stand down. Protect the command post. Wait for branch directors to parcel out assignments through the chain.”

So, the firefighters obeyed.

They watched the glow on the ridgeline grow brighter. They heard the explosions of propane tanks echoing down the canyons. They smelled the burning houses. They knew that water was abundant in the neighborhood swimming pools behind countless homes.

And many stayed in the parking lot.

Some played cards to pass the time. Some slept in their rigs. Nearly none broke ranks.

Micro-choice #2.

This choice was repeated a thousand times: “I will follow orders even when I can see the right thing to do with my own eyes.”

Nine months later, almost no one has come forward publicly to say, “We were parked at the beach doing nothing while the Palisades burned. Here’s the log. Here’s the text string.”

I can’t count how many Palisadians in town have their own war story of how firefighters didn’t step up on their block. Didn’t choose to tap the pools right in the backyards.

Day One was the roar. Day Two and Day Three were the slow betrayal.

But Exponential Causality is most visible when the wind eases—when the problem becomes solvable, and the only thing left to measure is judgment.

Day Two and Day Three were not dominated by a single wall of flame.

They were dominated by preventable ignitions—mini-fires on already-burned lots, smoldering root runs, fence lines and mulch beds, hot spots that should have been drowned.

The town became a field of lit matches.

The Methodist Church was still standing at 10:40 a.m. on January 8.

Photo from a video by MATT MCROSKEY

And for stretches of daylight, the Santa Ana fury relented. The air steadied—long enough for a window to open.

In that window, you don’t “fight the wildfire.” You interrupt the chain. Two firefighters, one hose line, ten minutes—done. A mini-fire dies before it becomes a structure—before it becomes a block.

Instead, on the second and third day, the Palisades lost schools, churches, businesses—and so many homes that had no business burning down.

One small action early collapses a branching future; one small delay multiplies it.

Micro-choice after micro-choice repeated itself across a map of neighborhoods: “We’re not assigned to that.” “Wait for instruction.” “That’s another division.” “We have no choice.”

It sounds like obedience. But in an exponential system, obedience to paralysis is complicity in outcome.

Because doing nothing is not neutral. Doing nothing is a decision with consequences. In a fire, the refusal to act becomes fuel.

Ten minutes early: a mini-fire dies in a puddle. Ten minutes late: an eave ignites. Ten minutes later: the attic flashes. Then the block feeds the monster.

So the question that remains is not, “Why did the fire start?” It’s, “When the window opened—when the winds calmed, and so many places were savable—who stood up?”

Where was the city and local leadership, where were local firefighters saying this was such bad judgment—and doing something about it?

I want to be clear. That doesn’t mean there weren’t many, many extraordinary firefighters, passionately risking their lives—in the thick of the fire.

Yet far too many engines and firefighters—enough to have saved countless homes—never left the staging lots.

The price? Your job and your pension are on the line if you break ranks with your union or department.

Here’s the truth.

Silence is a micro-choice. And, it too, compounds.

But the silence is wider than the parking lot.

It is also the silence of local leaders who had to have known that the reservoirs were empty, that many of the hydrants were antiquated, and that there was no adequate evacuation plan in place.

It’s their job to know these things.

Water and Power belong in this chain, too.

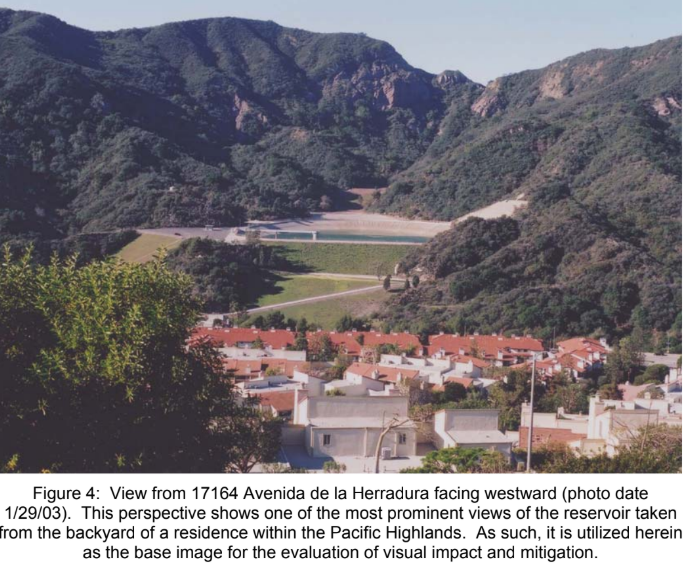

The Santa Ynez Reservoir—a critical water supply for a fire in this town—was completely empty when the Palisades Fire ignited. Empty because repairs and compliance decisions dragged on—leaving the town vulnerable during the worst possible fire season.

A blatant example of micro-choices with macro consequences—one more link left weak, one more “later” that arrived right on time.

And then there’s the city leadership.

Protecting a city from fire is the most primitive, non-negotiable duty of government.

Yet, year after year, the warnings were filed, the budgets deferred, the risks downplayed.

When the wind came, and the ember breathed, the failure was not one bad night. It was thousands of quiet nights before—thousands of meetings, votes, memos, and shrugged shoulders that collectively chose comfort over readiness, optics over preparation, the next election cycle over the lives on the hillside.

And when the monster finally roared down the canyons, the same leaders who had left the city defenseless now stood before cameras expressing “shock” and “heartbreak.”

Maybe some of them even did.

Sheep are not only the ones who obey bad orders.

Sheep are also the ones who give them— and the ones who, long before the fire, looked the other way while the flock went unprotected.

This is the terrifying truth of Exponential Causality laid bare in smoke and ruin. It doesn’t allow any of us to hide behind, “I was only following policy,” or “I didn’t know,” or “it wasn’t my department.”

Choices are not small. Obedience is not neutral. And silence is not safe.

In the end, the Palisades Fire was authored by every hand that held a pen and chose not to write the hard truth, and by every mouth that stayed closed when it could have sounded the alarm.

The Palisades Fire is the story of an ember leaders let live, and the moments when people could have stopped the next link—and didn’t.

Never again can we pretend we are only passengers.

We are all the authors.

And the story is still burning—in the choices we make next.

This was the start of the Palisades Fire on January 7, captured around 10:30 a.m. from a building on Sawtelle. The video below was captured several miles east around two hours later.

(Jimmy Dunne is a modern-day Renaissance Man; a hit songwriter with songs on 28 million hit records; songs, scores, and themes in over a thousand television episodes and many hit films; a screenwriter and producer of hit television shows; an award-winning book author; an entrepreneur—and his town’s “Citizen of the Year.” Reach out to him at [email protected].)

Brilliant.

Instead of beachwalks maybe the firefighters can get their exercise doing hydrant checks and cleanouts.

WONDERFUL!!

But some of these fire”fighters” did break ranks. Those of us up there for all three days of the fire can bear witness to several crews taking joyrides into the fires to take selfies, screwing around, and even worse, passively park and watch civilians scrambling to do their jobs for them. I have photos of several of these creepy non-responders seemingly having a great time while refusing to get out of their rigs to actually pic up a hose or even use their blankets to help us dampen the tiny spot fires that eventually consumed entire blocks. Doing nothing that day, was not an option. Even with orders….though obviously these joyriding non-responders weren’t even following them. It’s been a year now. Lets get the call logs and GPS positioning and lets hold our local fire fighters accountable for their actions during the hours this fire was extremely preventable. We cannot rebuild if these nonresponders are still in our stations.

Finn-Olaf,

I asked for the call logs from the LAFD through a public records request and was denied because of possible litigation. I also asked for CalFire’s logs (they took over at 6 a.m. on January 8)

and supposedly they’re working on that request. I would welcome any help in getting the LAFD records.

Sue