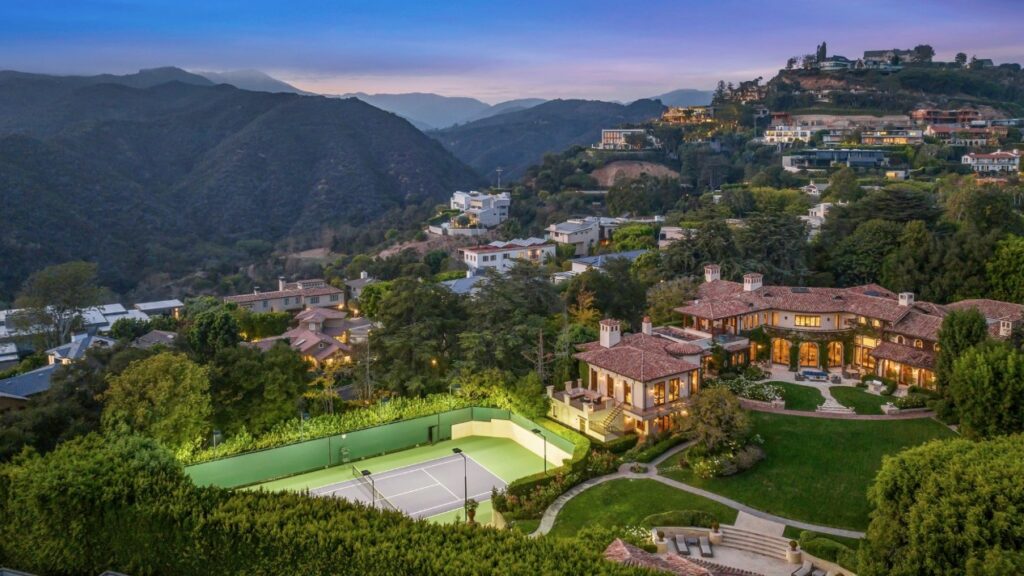

The “mansion tax” took effect in april 2023 and adds a 5.5 percent ranser tax on poperty sales exceeding $10.3 million (a four percent tax is added on sales above $5.15 million).

(Editor’s note: This story first appeared in the Westside Current on June 26 and is reprinted with permission.)

By JAMIE PAIGE

Two years after Los Angeles began collecting a tax on multimillion-dollar property sales, nearly all the money meant to combat the city’s worsening housing and homelessness crisis remains untouched—sitting idle in city accounts as homelessness worsens and construction stalls.

Measure ULA—nicknamed the “mansion tax,” even though it also applies to commercial and larger residential building sales—was approved by city voters in November 2022 and took effect in April 2023. It currently adds a 4 percent transfer tax on property sales above $5.15 million, and 5.5 percent on those exceeding $10.3 million. Supporters projected the measure would raise from $600 million to $1.1 billion annually to fund tenant protections, rent relief, and most urgently, new affordable housing.

Revenues have come in well below expectations, with the city collecting about $703 million in nearly two years. The bigger issue is the money is not getting out the door. According to an update presented to the ULA Citizen Oversight Committee last month, the City of Los Angeles has spent just $912,699—about 1.3%—on new multifamily affordable housing. Documents show a “Remaining Balance” of nearly $188 million in the “Affordable Housing Programs” pot.

By contrast, over $25 million has gone to homelessness prevention programs such as rent relief and eviction defense and the city is projected to spend $13.4 million in administrative expenses.

That means the city has spent roughly 15 times more on running the program than actually building the housing it was intended to create.

City officials initially blamed the slow rollout on legal uncertainty. In mid‑2023, property owners and anti‑tax groups—including the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association, the Apartment Association of Greater Los Angeles and Newcastle Courtyards—filed suit to invalidate Measure ULA.

On Oct. 26, 2023, LA Superior Court Judge Mitchell Beckloff dismissed those challenges, affirming the measure’s legality and clearing the way for funds to flow.

City Attorney Hydee Feldstein Soto said the ruling “upheld the will of Los Angeles voters.” Mayor Karen Bass acknowledged the lawsuit had prompted early caution but stressed that rent-relief and homelessness‑prevention programs had already begun.

Proceeding With Caution

City officials say an appeal of that suit still means they are moving forward with caution.

“Although court decisions have so far upheld Measure ULA, the litigation is still not fully resolved,” said Sharon Sandow, a spokesperson for the Los Angeles Housing Department. “That uncertainty prevented the city from making enforceable funding commitments for large-scale housing projects until this year.”

Yet critics contend that blaming the courts is a smokescreen. The city’s general fund earmarked $150 million for Measure ULA-related spending—money not restricted by litigation—but less than half of that has been spent.

Additionally, the City Council delayed adopting permanent guidelines for ULA funding until December 2024, more than 20 months after the tax took effect. In the interim, the city launched just six of 11 authorized programs—only one of which focused on housing production.

To date, Measure ULA has committed funds to nine affordable housing projects totaling 795 units.

Yet critics say these numbers paint a troubling picture. They include Mott Smith, Chairman of the Council of Infill Builders, who analyzed the city data.

“Almost all of these projects were already in the pipeline before ULA passed,” Smith told Westside Current. “ULA is plugging funding gaps—not launching new construction.”

Of the nine projects, just two have finalized funding agreements with the city. Five have pulled building permits—but four of those did so in February 2022, months before ULA was even on the ballot.

Smith, who also teaches real estate development at USC and serves on several city boards, said ULA’s own requirements make it incompatible with standard housing finance models.

Specifically, ULA mandates that any project receiving funds must remain permanently affordable and may never be sold to any entity that is not 100% nonprofit owned. “That effectively disqualifies most developers,” Smith said, “because affordable housing deals are usually built using partnerships with for-profit entities to access capacity.”

Challenge for Lenders

The strict resale and affordability covenants, Smith explained, violate terms often required by commercial lenders. For example, banks that provide construction and permanent loans must be able to recover their losses in the event of foreclosure—typically by selling to the highest bidder. ULA’s restrictions prevent that, making the deals unworkable for banks.

That may be partly why so much of that nearly $188 million dedicated to Affordable Housing Programs currently remains unspent.

“The issue isn’t legal—it’s structural,” Smith said. “ULA funding is simply not usable in most affordable housing finance stacks.”

Despite the current backlog, city officials have promoted a new cycle of ULA allocations, the “Homes for LA” Notice of Funding Availability (NOFA). It is expected to release $316 million later this year.

But Smith remains wary. “Most projects listed in the 795-unit count haven’t closed financing, nearly half haven’t started construction, and the ones in process predated Measure ULA.”

The 15-member citizens oversight committee, created to monitor Measure ULA’s implementation, continues to defend the slow rollout. Members cite hundreds of meetings, coordination efforts, and an independent audit expected later this year. They say money has been spent to, among other things, protect tenants from harassment and keep them in their units.

But critics argue the committee lacks both independence and meaningful authority.

Oversight of Measure ULA’s $700 million in revenue does not fall under the authority of a city official or an independent auditor. Instead, it is handled by a private consultant operating under the title of “Interim Inspector General”—a structure that raises concerns about the strength and independence of financial oversight. Initially awarded a $250,000 contract, Estolano Advisors, the consultant brought on for the oversight, has seen its compensation balloon to more than $750,000, with monthly retainers rising from $20,000 to $30,000.

Smith says he is not opposed to Measure ULA’s goals. In fact, he says he wants it to succeed—but believes reforms are essential.

“Most voters thought they were approving a mansion tax,” Smith said. “They had no idea it would choke off investment in multifamily, manufacturing, and commercial redevelopment.”

He warns that unless the city makes urgent structural changes to the program, a 2026 ballot initiative backed by the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association could repeal the measure entirely.

“We’re at a crossroads,” Smith said. “We can either fix ULA to make it work, or lose it altogether. Right now, we’re doing neither—and families, builders, and the city are all paying the price.”

Why is every single idea good or bad immediately mired in controversy and or bureaucratic nonsense and/or petty fiefdom so that nothing ever gets done.

Giant sigh.

The money is still in the bank because they haven’t decided which one of Karen Bass’ friends should get it.

“Oversight of Measure ULA’s $700 million in revenue does not fall under the authority of a city official or an independent auditor.”

“ULA funding is simply not usable in most affordable housing finance stacks.”

Really not surprised at all about any of this. I’m so glad I moved out of California.