By TIM CAMPBELL

A common reaction to the many scandals surrounding homelessness in LA is that they reflect the corruption that permeates the entire system.

Terms like “homeless industrial complex” are used to describe the web of interconnected leadership that controls the billions of tax dollars spent on homelessness. Certainly, there is plenty of evidence that seems to support this view.

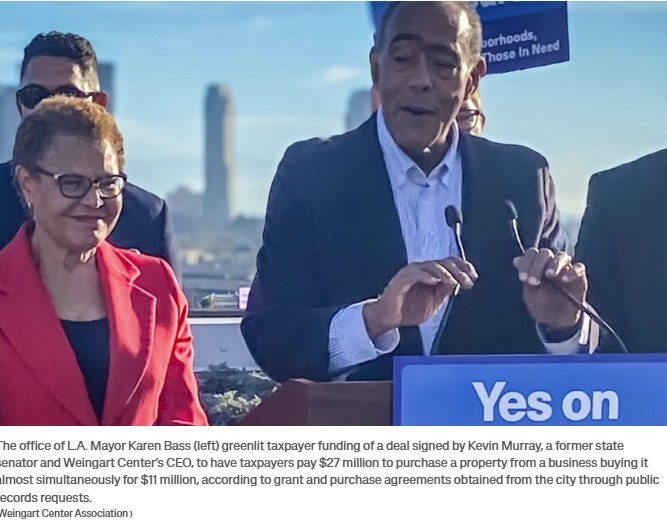

The recent indictments of two people on charges of fraud related to the acquisition of properties using Project Homekey money is a good example. As described in a recent LAist article, a developer, Steven Taylor, bought a senior housing complex in Cheviot Hills in 2023 for $11 million. Even as the purchase was in escrow, Tyler was negotiating with officials from the nonprofit Weingart Center to buy the property for $27 million, based on what federal prosecutors call artificially inflated assessment reports.

Soon after the indictments were made public, the Weingart Center’s Board suspended CEO Kevin Murray and Real Estate Director Ben Rosen. Although neither have been charged with any crime, there are questions about how or why the Weingart Center would agree to pay more than twice the market value for the Cheviot Hills property.

In a prime example of how tight-knit the leadership of LA’s homelessness system is, Murray recently stepped from the governing board of the L.A. County Affordable Housing Solutions Agency (LACAHSA), a fairly new (and obscure) agency that makes funding decisions for the use of revenues from the County’s Measure A sales tax initiative.

In other words, Murray was sitting on a Board that made decisions about spending tax dollars on just the sort of transaction that is now under federal scrutiny. It is also worth noting Murray was appointed to LACAHSA’s Board by Mayor Karen Bass; the two have been political allies for years.

The Cheviot Hills scandal is just one of several that have been exposed in the last year or so.

I’ve written about former LAHSA CEO Va Lecia Adams Kellum approving contracts to the NPO where her husband is a senior manager. LAist ran a series of stories on how the 2024 and 2025 PIT counts potentially undercounted thousands of unhoused people because managers excluded troublesome counts instead of resolving them, and how whistleblowers say LAHSA’s executives cooked the numbers to make the Mayor’s Inside Safe look more successful than it is. Then a March 2025 release of a comprehensive assessment of the City’s homelessness programs exposed the serious risk of fraud, as audit firm Alvarez & Marsal (A & M) found the City and LAHSA regularly pay for services with no verification.

Through all of these scandals, it seems our leaders have expended most of their energy defending their allies in large nonprofits or fighting reform in court, rather than addressing the problems exposed in a host of reviews, audits, and news reports.

Surely, we need no more proof of a corrupt system than the tenacity with which local leaders defend it. But accepting LA’s homelessness system is corrupt is not enough. Unless we understand the nature of that corruption, we cannot know the kind of reform the system needs.

There are many types of corruption. The Cheviot Hills sale is an example of plain fraud. Approving contracts to a spouse’s nonprofit is a serious ethical breach. Continuing to defend a system that dumps people in poorly-run shelters or abandons them in spartan housing is a stunning moral failure.

But the real problem with corruption in homelessness is how thoroughly it is ingrained and how mundane it is. It is what I call “organic corruption,” a type that has no clear beginning, but grows and evolves over time to protect business as usual.

Most of the people participating in an organically corrupt environment have no conscious awareness they are part of broken system. An accounts payable clerk who issues a check to a nonperforming provider isn’t dishonest; he or she may have obtained all the proper approvals and checked for a signed contract before sending payment. The corruption exists far above his or her position, with the executives who wrote a contract that pays for processes instead of results, and with the nonprofit leaders who influenced how that contract was created.

Organically corrupt systems do not start out that way. Thirty years ago, Housing First seemed to be a promising solution to homelessness. Giving people stable housing and then providing them with the services they need to live independently, by its nature, means they are no longer homeless.

However, as policymakers increasingly focused on housing, they turned away from other elements like transitional shelters and support services.

As the National Interagency Council on Homelessness said in 2020, housing no longer became part of a toolbox of solutions, it became a goal unto itself. Pushed by the narrative that “housing is a human right,” creating new housing became the official policy of most local governments.

Housing took on a moral dimension wholly outside of its place as a homelessness solution. To question the need for housing as a solution equaled “hating the homeless.”

Not coincidentally, advocates and developers realized there was money to be made in housing, not only in its construction, but in its acquisition and support as well. Hence, the seeds for schemes like the Cheviot Hills deal were born.

Housing, or more specifically permanent supportive housing, became a lucrative source of revenue for service providers. The City, the County, and LAHSA pay hundreds of millions in contracts for an array of services, from meals to psychological support for people in supportive housing.

It didn’t take long for providers to realize the best way to ensure a continuous revenue stream was to control the policy-making narrative. Nonprofit leaders like Dr. Va Lecia Adams Kellum, CEO of St. Joseph Center, became a political ally of mayoral candidate Karen Bass (one of Bass’ daughters works for St. Joseph).

Lena Miller, CEO of Urban Alchemy, is known for her political ties in San Francisco and LA, explaining why both cities continue to award the NPO contracts despite serious questions about its operations.

To further cement their position in policymaking, many nonprofit executives use their political connections to get appointments as members of decision-making bodies.

I already mentioned how Murray held a position on LACAHSA’s board while being a CEO of a nonprofit that could benefit from that board. He is hardly the exception. LAHSA’s Commission is made up of advocates and pro-building representatives with the exception of Justin Szlasa. No member is a medical expert on mental illness or substance abuse. As a former City Controller, Wendy Greuel is well-versed in performance management, but she has shown little inclination to hold LAHSA’s vast constellation of providers accountable for their outcomes.

As A&M and the County Auditor described in two separate reports, the influence of nonprofit providers is so insidious, that the City and LAHSA see their primary mission as paying them as quickly as possible, while asking as few questions as possible.

A&M’s report said contract administration is so lax, providers can virtually define their own performance requirements. County auditors found LAHSA was paying NPO’s without contracts and failed to recoup cash advances paid to providers, among many other problems.

In this environment, organic corruption has flourished.

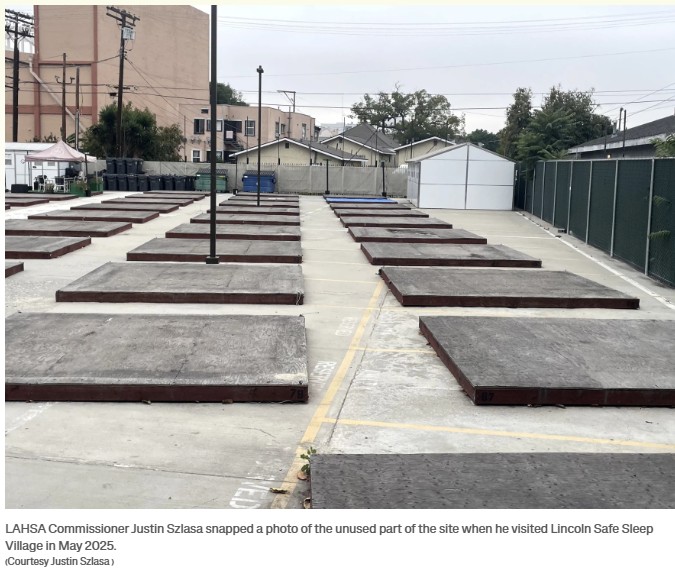

A perfect example is a recent LAist story about a Safe Parking area in L.A. For at least a year, LAHSA has been paying Urban Alchemy for managing an 88-space safe parking site. The nonprofit only provided 44 spaces and it’s unclear how many of those were actually used.

There seems to be some question as to who was responsible for reporting the reduction in parking capacity, but because LAHSA pays for processes instead of outcomes, it continued to pay for 88 spaces until inspections by LAHSA Commissioner Szlasa and the federal court’s Special Master Michele Martinez. As the LAist story details, LAHSA and Urban Alchemy pointed fingers at each other.

Apparently, the thought of proactively checking UA’s performance never entered the mind of LAHSA’s contract management staff.

It is an environment where Kellum, in her role as LAHSA CEO, approved contracts with her husband’s nonprofit, and where an “independent investigation” by LAHSA showed she violated no ethics policies (of course it helped LAHSA didn’t adopt such policies until after the contracts were made public–you can’t violate a policy that doesn’t exist).

Investigators said the contracts were proper since LAHSA contracted with the NPO before Adams Kellum was CEO. That is nonsensical; the previous CEO didn’t have a personal relationship with a senior manager at the nonprofit. Indeed, a follow-up investigation by LAist found Adams Kellum approved contracts with her old nonprofit, St. Joseph Center, just a few months after taking her position with LAHSA; this was a violation of state ethics rules.

This environment creates a mentality where it’s okay to contract with a spouse’s nonprofit because “we always have,” and whether or not a provider is actually managing the number of safe parking spaces its contracted to manage isn’t important. What is important is to control the narrative and protect the system at all costs.

Organic corruption evolves incrementally.

Each decision made to protect a provider may seem reasonable in isolation, but each can be used to justify increasingly questionable steps. It is also self-justifying.

Nonprofits provide important services and housing is a human right, therefore anything done to benefit a favored NPO or any expense paid for housing, no matter how high, is for a higher cause. This is the mentality that justifies keeping proposed shelter and housing projects out of the public sphere until the very last minute and then using epithets like “hating the homeless” when community members rightfully object.

Most of the people who are part of an organically corrupt system can’t see the inherent dishonesty of what they’re doing. Dr. Adams Kellum is a well-educated and experienced leader who would probably never intentionally do anything dishonest.

Rising up through the milieu of organic corruption, it would never occur to her that contracting with her old NPO may be ethically questionable. On the other hand, someone as opportunistic as Lena Miller sees an environment ripe for making money, where lax management and blindly supportive leaders make it easy to take advantage of the system.

Unfortunately, the longer corruption lasts, the more embedded it becomes and the more blatant it is. So, you begin to see things like the Cheviot Hills scheme, or you stop submitting documents or following up on expired contracts because nobody cares anyway and you can be confident, you’ll be paid. It also becomes more aggressive when challenged. That’s why we saw the spectacle of Bass and Councilmember Raman literally running from City Hall to the County Hall of Administration to try to stop the Board of Supervisors from defunding LAHSA. Defending the status quo is the ultimate goal.

The biggest problem with an organically corrupt system is that it cannot be reformed.

Consider the accounts payable clerk. He or she receives an invoice from a provider. A program manager has already approved the invoice for payment. The supporting documentation shows the provider completed all the processes required by the contract, and the contract was approved by your Commission or Council. Never mind the contract was partially created by the nonprofit the clerk is paying. You pay the invoice regardless of real outcomes. There is no whistleblower because nobody has done anything wrong, at least procedurally. Despite the fact taxpayer money has been spent for no real benefit, all the paperwork is in order, and invoices have been paid based on the same criteria for years.

Organically corrupt systems must be dismantled and rebuilt.

Nonprofits need to be treated like contractors instead of partners; contracts must be structured around outcomes instead of processes. Boards and Commissions need to balance membership between advocates and subject matter experts in medicine and program performance.

And Housing First has to be relegated back to its role as one element in a larger toolbox of solutions.

If we de-emphasize the construction of new housing, then dishonest developers like Taylor wouldn’t have as many opportunities for fraud as they do now. Finally, we need to raise our expectations of our elected leaders. They need to represent the public good, and that includes the housed and unhoused, and abandon the narrative that has sustained the corrupt system we’ve endured for more than two decades.

I wish a shortened edited version of this article would get published in the LA TIMES paper.

Great reporting Mr. Campbell

Contracts must have performance benchmarks that need to be met and also ironclad clawback clauses. Performance and integrity must rule the day, and lawsuits or prison for those that willfully violate them.

Excellent article. I have pretty much stopped reading any stories on homelessness, as it is so dispiriting. The talking heads talk, the non-profits spend money with no accountability or results, and our tax dollars pay for all the of corruption and ineptitude. I don’t have any realistic solutions myself, but then I was not elected to do that. Our politicians were. Remember Garcetti’s 10,000 homes in 10 years? If it weren’t so sad it would be funny. Bring in the clowns…

Despite what comes of these investigations the same politicians responsible will still be re-elected, which is the Los Angeles way.

As a Palisadian now reduced to renting in West LA I walk 3 blocks to work every day and pass at lease 4 homeless passed out on the sidewalk. LAPD patrol cars cruising by in abundance but never pick up anyone. Los Angeles is now a dangerous Democrat city.

The picture accompanying the article tells you everything you need to know. Smiling Mayor Karen is just thrilled with herself because she’s done something wonderful “for the people”. Never mind the corruption, nepotism, self-dealing, ineffectiveness, and lawlessness. As long as Smiling Mayor Karen and her cronies feel good about themselves… that’s all that matters.

“Most of the people participating in an organically corrupt environment have no conscious awareness they are part of broken system. ”

Complete BS. The people at the top know EXACTLY what they’re doing and they’ve conditioned their staff to not ask questions or think for themselves. They do this by playing on their staff’s egos and telling them how wonderful they are and how they should be proud that they’re part of the a great team that’s doing so much good for the less fortunate.