People can still hike on the steps in upper Rustic Canyon that were built to maintain nut, citrus and fruit trees on a ranch that was designed for the Stevens’ family.

Photo: Stewart Slavin

By STEWART SLAVIN

What’s the real story behind Murphy Ranch?

The long-abandoned survivalist sanctuary tucked into the hills of Pacific Palisades has spawned one of L.A.s wackiest urban legends — that of Nazis building a utopia there during the 1930s that Adolph Hitler planned to use as his “Western White House” after victory in World War II. Even historians bought into it.

In an effort to separate myth from reality, I had the help of the grandson of owners of the ranch during that time period to piece together what really happened there.

The actual story is stranger than fiction, featuring one of America’s richest families and a Rasputin-like faith healer from Norway who most probably triggered the Nazi myth.

Our journey begins in 1918 when Winona Bassett, a beautiful, Stanford-educated Pasadena socialite, attended a dance for military personnel. Also present was Norman Stevens, a handsome instructor in the Army’s Service Balloon Corps. The pair met and sparks flew. They began courting under the watchful eye of Winona’s protective mother, Theophila Bassett.

Two weeks before their wedding, Winona sprung the news on Norman that her family was one of the wealthiest in the country, making their fortune in the thumb tack and nail business in Chicago, and she had inherited $20 million with more on the way. That’s an amount worth well over $1 billion in spending power today. (To Norman, $1,000 was a lot of money.)

Despite her vast wealth, the couple started out living in a comfortable, though modest, home Norman had bought with money from designing a refinery for a local oil company. Stevens was a talented engineer who had built and flown his own biplane and glider before attending MIT though he later dropped out to join the Army.

Not satisfied with their living arrangement, Winona’s mother built one of Pasadena’s finest homes across the street for the couple. Norman swallowed his pride and he and Winona moved in.

We jump to 1931 when the couple’s 4-year-old son, Robin, was stricken with the skin infection impetigo, which at the time could prove deadly, and he had to be isolated because the condition was extremely contagious. For a year, Winona followed the treatment prescribed by Christian Science, which was Theophila’s religion, and involved a lot of praying but no doctors. When the praying failed to improve the condition of the boy who was then near death, Norman took over and brought in a Norwegian healer he heard could do wonders.

The healer, Conrad J. Anderson, bent over Robin’s bed and touched his sores. Within two weeks, nearly all the sores were healed, and Robin was cured. Winona promptly gave up Christian Science and adopted Anderson as the spiritual guide for the Stevens family. In her eyes, Anderson could do no wrong.

The Stevens may have had second thoughts had they known that a year earlier Anderson was sentenced to 90 days in jail and fined $500 for practicing medicine without a license. The sensational case drew headlines because Anderson had been accused of treating a woman for a serious illness with cosmic rays emanating from his fingertips. He had charged the woman and her husband $1,200 but she died a short time later.

After gaining the Stevens’ confidence, Anderson told them another global war was coming but that he could help protect them from it if they followed his plan. He urged the couple to build a self-sufficient sanctuary in hills north of Los Angeles.

Winona heeded the call, and in 1933 or 1934 purchased 41 acres from Jessie M. Murphy in the upper reaches of Rustic Canyon next to the properties of Will Rogers and Anatol Josepho, the inventor of the Photo Booth who would donate his land for a Boy Scouts camp in 1941.

At the time, Norman Stevens was in Canada looking after mining interests. Winona wanted to keep a low profile, so she worked out a deal with Jessie Murphy for her to keep the property under her name until the early 1940s when Winona’s name appeared as owner of record. Under the agreement, Norman was listed as chief engineer of the ranch, and his name even appeared in correspondence with neighbor Will Rogers when the cowboy humorist raised concerns about the diversion of water from a creek that went through both properties.

The local newspaper, the Palisadian, reported on May 25, 1934, that “at present there is a force of 50 men or more busy leveling and terracing the canyon sides and building a cement flume the entire length of the canyon to care for flood waters. Reservoirs for water, of which the estate has its own supply, and for crude oil, have been built. A high wire fence surrounds the entire tract. Architects Plummer, Warden and Beckett are now working on plans for the building proper, which is to be in the Spanish Mission style. Engineer N.F. Stephens is supervising the work.” (The commission was reportedly the first for Welton Beckett, who later designed the Capitol Records building and Los Angeles Music Center.)

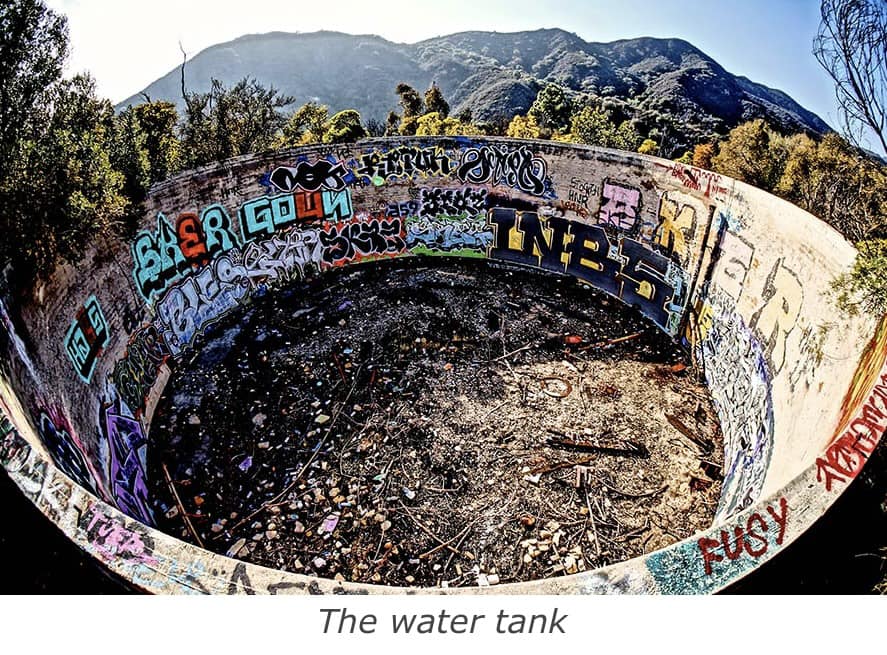

Nine concrete staircases, the longest 512 steps, were built into the side of the canyon to maintain some 3,000 trees — nut, citrus and fruit. The concrete water tank, supplied from wells, held 395,000 gallons and a steel fuel tank 20,000 gallons. A power station with double generators was large enough to supply a small community. Paved roads were built along with an elaborate greenhouse and huge food locker dug into the bank of a stream providing natural refrigeration.

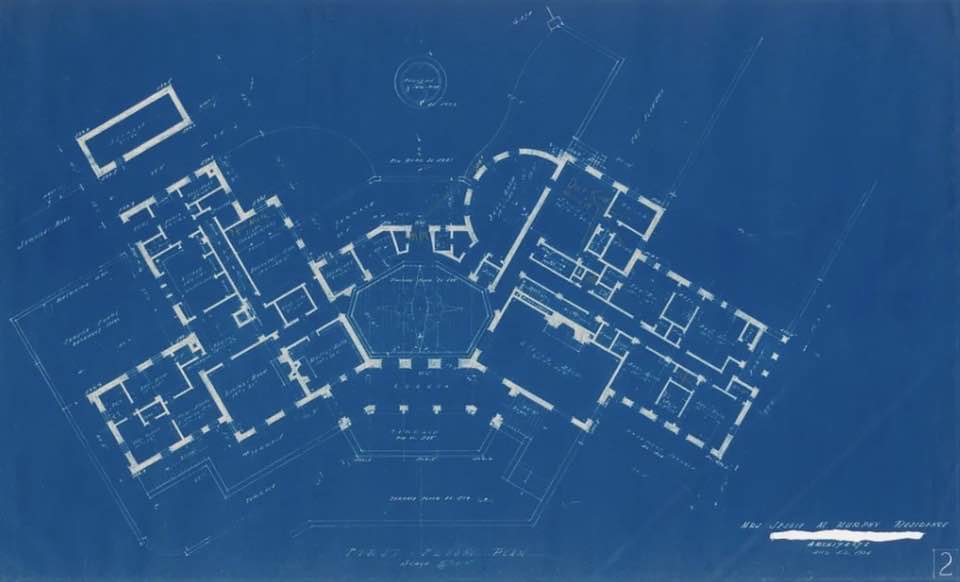

Over the years, various architects made blueprints for a palatial, four-story mansion, culminating in a 1939 plan by black architect Paul Williams. The neoclassical design included 22 bedrooms, detached servants’ quarters, multiple libraries and reading rooms, a children’s dining room, and in the basement a swimming pool, gym and workshops. A two-story barn would include a dairy, butchering facility and commodious pigeon loft. All of it was planned for the Stevens and their four children.

Construction of the facilities and other infrastructure took eight years to complete, but the mansion was never built. Cost of the entire project, including purchase of the 41 acres, was approximately $900,000 according to Norman Stevens. During the building work, he traveled back and forth to the ranch from the Stevens’ homes in Pasadena and later Hermosa Beach, with the whole family moving to the spread on Thanksgiving Day, 1942.

The wrought-iron gate to the entrance of Murphy ranch survived nearly 80 years before it was torn down by the city in 2016. Photo: Stewart Slavin

Faith healer Anderson, meanwhile, took up residence there a couple of years earlier, bringing with him two wealthy women followers, and later a third, who were tasked with milking the cows, collecting eggs and other farm chores involved with running the ranch.

Two of the Stevens children, Robin and Carlile, recalled that Anderson was a womanizer and abuser who cruelly exploited the family and instilled fear in them. At the same time, they described him as a charismatic party host often surrounded by women followers who did his bidding.

But he was also a “powerful and evil” man, according to the Stevens grandson, who nearly succeeded in getting Norman and Winona to sign over to him the ranch and all their assets should Anderson outlive them.

At one point, he instructed a woman follower to poison Norman’s food with arsenic on a daily basis. The plan ultimately failed when Norman didn’t die. Despite his attempts to control the family, Winona still trusted the mysterious Norwegian with his supposed magical healing powers.

Anderson himself miraculously survived a steep fall down the canyon in his car shortly after his arrival at the ranch in December 1938. According to a news report, Anderson’s “heavily built automobile” failed to negotiate a sharp turn near the ranch and plunged nearly 500 feet to the canyon bottom.

“The car must have turned over many times before it reached bottom,” the report said. For two hours the fire department labored to lower more than 1,000 feet of rope and managed to bring Anderson to the top with a specially constructed stretcher. He was dazed but escaped major injury.

Now it’s time to take on the urban legend claiming that Nazis ran Murphy Ranch and how it began.

There is evidence the source of the misinformation began with a one-page affidavit written by UCLA music professor John Vincent that had been requested by historian Betty Lou Young for her 1975 book, “Rustic Canyon and the Story of the Uplifters.”

She had been leery of his claims of Nazi involvement and asked for the documentation. Vincent, a composer and head of the UCLA Music Department, also was a director of the Huntington Hartford Foundation and negotiated the $100,000 purchase of Murphy Ranch from the Stevens in 1949 for use as an artists’ colony.

The affidavit was suspect from the outset.

In it, Vincent claimed to have met the Stevens while they were living in a steel garage at the ranch in 1948. But that is disputed by the couple’s grandson, Stanton Stevens, who said they had moved to a property in Ramona in 1945. Also, Vincent incorrectly referred to the couple as Winona and Norman Stephens, which is repeated in the book and later versions of the urban legend.

Betty Lou Young wrote that rumors were starting to swirl in lower Rustic Canyon that something strange was going on at Murphy Ranch in the 1930s. “A workman told tales to his neighbors of a self-sufficient farm in diligent operation, Nazi-style paramilitary exercises and drills, and the presence of an overbearing German named Schmidt.”

Based on Vincent’s affidavit, Young said the ranch was envisioned as “a sort of National Socialist Utopia, financed by Winona and Norman Stephens — he an engineer with silver mining interests (actually, he had no such interests), and she the daughter of a wealthy industrialist.”

“Mrs. Stephens was intrigued by metaphysical phenomena and fell under the influence of a very persuasive gentleman who convinced her that he had supernatural powers,” the book said. “He also convinced her that the end of the world was at hand, that as a result of the imminent struggle between the United States and Germany,

California would be devastated, and that the United States would inevitably be destroyed by the might of Germany.”

“The only salvation, Schmidt told her, was to establish a completely self-sustaining community where a group of chosen could survive the bombings, defend themselves, and remain for at least a year until it would be safe to emerge and form a nucleus to repopulate the United States.”

The book said an estimated $4 million had been invested in the ranch, while the actual figure, according to Stanton, was $900,000.

The Nazi plan fell apart, Young said, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

“The canyon Svengali was promptly apprehended and identified as Herr Schmidt, a Nazi spy who had hidden powerful shortwave radio equipment on the ranch property and was sending clandestine messages to Germany. With no public furor, he was put in prison where he died before coming to trial,” Young wrote. As many as 50 of Schmidt’s followers were arrested with him, some unsubstantiated reports claimed.

Betty Lou Young wrote that “no living soul ever seems to have encountered a flesh and blood Jessie Murphy.” Randy Young expanded on the claim years later by speculating that “Murphy” was actually a front for Nazi groups that footed part or all of the bill for the ranch.

But Jessie M. Murphy was no figment of the imagination. According to Winona’s daughter, Theanne, her mother had become good friends with Murphy and she and her mother visited the previous ranch owner in her apartment in Santa Monica when she became ill. Theanne was attending Canyon Elementary School at the time with her brother Carlile.

Randy Young also estimated that up to 40 local Nazis may have lived on the secretive property from 1933 to 1945. “It was a Silver Shirt operation of the American Bund movement,” said Young, who was the photographer for the book and followed his mother as president of the Pacific Palisades Historical Society. Randy admitted, however, he had scant evidence for the claims he said were based mostly on what was passed down orally.

Norman and Winona Stevens were also alleged to be Nazi sympathizers and members of the American Socialist Party, all derived from the writings of the Youngs or John Vincent.

The Stevens grandson vehemently denied the claim, pointing out that Norman worked on fighter planes at Douglas Aircraft as a quality control engineer which would have required security clearance. Two of the couple’s boys, Dale and Robin, went off to war in Europe and the Pacific to fight the Nazis and Japanese, respectively. The oldest boy, Dale, was awarded a Purple Heart and was a driver for Gen. George Patton.

Stanton Stevens, in interviews with family members who lived on the ranch, said no one remembers Anderson having allegiance to Hitler, or mentioning Nazis. At one point, the Scandinavian healer told the family he could use his black magic to stop any Japanese invasion into the canyon. “I will use my powers to turn their rice into rat droppings,” Anderson reportedly said.

And there was no Herr Schmidt or goose-stepping Silver Shirts on the property carrying out marches and drills, Stanton said. Norman Stevens would have noticed any suspicious activity on the ranch during his frequent visits during the 1930s.

How the Nazi rumor first got started is unclear, but it’s not too far-fetched to conclude that the over-bearing Anderson with his mystical beliefs may have conjured up a Herr Schmidt in the minds of suspicious and fearful neighbors in a Los Angeles faced with a proliferation of local Nazi groups during the Depression years.

The legend grew like Pinocchio’s nose to a point that Hitler himself was said to be planning to make Murphy Ranch his Americas vacation home when the Nazis achieved victory. “When the Nazis were thinking grandly about Hitler’s inevitable takeover of the United States — once he had finished with Europe — the Murphy Ranch was going to be like San Clemente for Richard Nixon or Mar-a-Lago for Trump, only better sited for international routes,” USC historian Steven J. Ross told the Palisadian-Post in 2018.

In 2014, the Stevens’ two surviving children who lived on the ranch with Anderson had a meeting with Randy Young, who had been telling the tale of Murphy Ranch being a Nazi enclave in newspaper interviews, on television and in lectures for nearly 40 years.

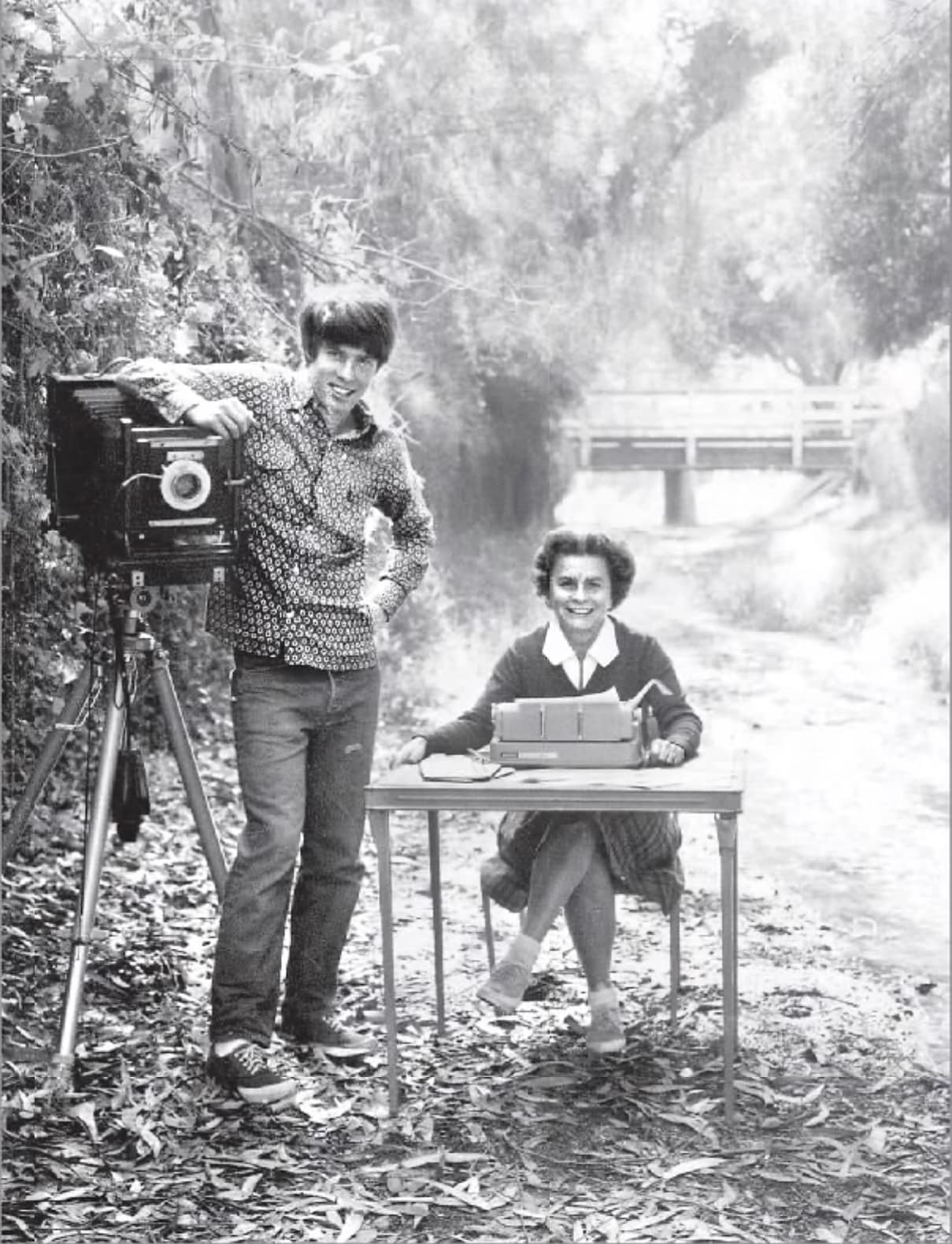

Carlile, (left), and Robin Stevens met with local historian Randy Young, to debunk the myth that Murphy Ranch was intended for Nazis. Photo: Stewart Slavin

After listening to the stories and memories of Stanton’s father and Robin, then 86, Young believed them, Stanton said. “He (Randy) said the hairs on the back of his neck were standing up” after hearing the real history of the ranch, Stanton added.

“My uncle begged him in tears to stop calling our family Nazis and Young agreed to stop repeating the story,” Stanton said. “He is serious about being accurate as a historian. He is as dismayed as we are at the exaggerations added to the story as the yeas have gone by.”

Today, there are few reminders of the ranch whose grand plans were never realized. Anderson died on the ranch in 1943. By the time of Winona’s passing in 1954, nearly all of the family’s fortune was gone.

The 1978 Mandeville fire destroyed most of the structures on Murphy Ranch, now accessible only by a 3.85-mile hike and concrete staircase of 512 steps. The big water tank, gate and remains of the steel building were torn down in 2016 for safety reasons by the city of Los Angeles, which now owns the land. The concrete powerhouse, which Carlile once tended, is the only structure left standing on the ranch property, which is continually painted over with graffiti.

This building was the source of the power used on Murphy Ranch. It is the lone building still standing on land, now owned by the City of Los Angeles.

Stanton Stevens is author of The True Story of Murphy Ranch, Nazi Nonsense in Los Angeles.

Stewart Slavin, who attended Palisades School (class of 1964), graduated from UCLA. He spent his life globe-hopping, covering news for the UPI in the far reaches of the world. After retiring, he relocated to North Carolina. His second book Memory-Go-Round — Ride of a Lifetime, was released in June.

Fantastic story. Randy Young recently spoke about the Nazi’s at Murphy Ranch at the Thomas Mann house. Glad to hear it is fiction.

Great story! Always nice to learn historical facts about our wonderful Pacific Palisades community!

Wow, what a great story Sue! You did a ton of research. I always believed the Nazi bunker story and used to hike down there all the time in my younger days. That bldg you say was the power source used to be covered in swastikas! I was so fascinating by the whole place, but never knew any of this back story. What i don’t understand is why the descendants of the Stevens family didn’t inherit the land that their grandparents purchased? I’m sure it would be worth gazillions of dollars now. Also wonder why the city of LA doesn’t do anything with it? Would have been very cool had that four story mansion been built! Thanks for the research and for clearing up the mystery.

Nancy,

It was former Palisadian Stewart Slavin who did the research and wrote the piece–It was an amazing story.

Sue

Nancy, the family lost most of its fortune and needed money by 1949 when it sold the property to The Huntington Hartford Foundation for $100,000 at a huge loss. They had spent $900,000 on the ranch. Some of the family’s money was lost due to bank failures during the Depression. It’s now a city park but L.A. has no plans to improve it, especially after the 1978 Mandeville Fire that destroyed most structures on the ranch.

Again the whole Nazi story is complete fantasy.

The guy made it up for 40 years and did interviews

because he was crazy.

You seem to forget that the Bel-Air fire of “61 also went all through there too.

I’m from West Los Angeles born and raised.

I’m fourth generation

There were no Nazis in West Los Angeles whatsoever

There was nobody here Sue.

Poor people lived in Pacific Palisades until the 1980s

That’s why US C is in downtown because the whole town with money lived in Hancock Park.

Alfonzo Bell and Mulholland were not Nazis

It’s all made up from people in Hollywood after World War II to sell movies.

It’s also ridiculous to try to say they were Nazis here.

there was nobody here