(Editor’s note: this story was first published on September 11 and is reprinted with permission.)

Trash from the roadside has been collected by volunteers and is waiting for the City to collect it.

Photo: JILL MATHER

By JAMIE PAIGE

Retirees clean every day. Caltrans says it’s cleaning more than ever. Los Angeles is still filthy.

CANOGA PARK — On a recent Monday morning, Jill Mather parked at the base of a steep hillside where partygoers had been tossing cans and bottles for months. Councilmember John Lee’s office had asked for help. Mather, founder of Volunteers Cleaning Communities, handed out grabbers and yellow safety vests, then eyed the slope.

“It was a massive, steep hill,” she said later. “We cleaned up an insane amount.”

With just three volunteers, they bagged what they could reach and told Lee’s office the rest would require a different kind of crew.

The work is a snapshot of how VCC, and other volunteer groups, operate across Los Angeles, trying to fill gaps in the cleanliness map: a daily grind of clearing the mess from sidewalks, gutters and parking lots, with add-on jobs when neighbors or agencies call.

Their small victories are visible in cleaner sidewalks. But just as visible is what requires their involvement in the first place: a city and a county where trash seems as permanent as palm trees, and where all the taxpayer-funded clean-ups and employees only seem to address a portion of the problem.

We wanted to know why Los Angeles looks so dirty, and what we found is there isn’t one straightforward answer — except, perhaps, the people living in it.

But the roads still look like dumps

Is Los Angeles dirtier than other cities? There are some indicators beyond personal observation, though they come from private companies, as opposed to in-depth university research reports.

A recent study by carpet cleaning company Oxi Fresh tabbed Los Angeles/Long Beach/Anaheim as the second-dirtiest metro area in the United States (trailing New York/Newark/Jersey City). Another report, by lawn care company Lawnstarter, also ranked Los Angeles as the second-dirtiest city in the country (this time San Bernardino was first), citing factors including air quality and near-roadway pollution.

For many Angelenos, the view from the wheel confirms that. On the 405, the 110 and the 10 freeways, debris consistently lines the shoulder: tarps flapping, Styrofoam clinging to the fence line, a stained mattress. Then there is the irony of the $90 million Annenberg wildlife crossing over the 101 being surrounded by trash.

Mather says city streets are “equal if not worse”—the kind of mess drivers miss at high speeds but that you see on foot: trash packed into bushes, gutters, parking lots and medians. That’s where VCC spends weekdays, block by block, bag by bag.

Illegal dumping multiplies the mess. Mather ticks off what her crews see most: construction rubble, landscapers’ bags, tires. On the ground, that surge leads to vermin, hazards and fire risk.

There’s a simple tool residents don’t always use: 311. Mather repeatedly tells neighbors to bag what’s safe and accessible and call or use the 311 app for pickup. The city will also clear bulky items for residents (think that old couch or refrigerator), and the service is free.

But as the Current reported earlier this month, 311 doesn’t always work as intended, and that may be making the problem worse. Residents have complained of faulty geo-tagging, requests being marked “closed” without service ever being completed, and other glitches that leave trash in place.

There’s also just response times and accountability. The City Controller’s 2021 “Piling Up” audit found average response times of five days and enforcement hampered by too few cameras and prosecutions. Four years later, residents report the same hot spots—and the data suggest the problem has only grown.

Those failures are showing up in the numbers. Illegal-dumping complaints jumped 36% in January and February 2025 compared with a year earlier—more than 22,000 complaints in two months, according to USC’s Crosstown analysis. Complaints are up, not down.

Encampments are a major trash source

Encampments are another major source of debris along freeways and on city streets. “When you clean a homeless encampment, it’s… thousands and thousands of pounds of stuff,” Mather said. She recently coordinated the removal of nine truckloads from three cleared camps with Los Angeles Sanitation (LASAN) trucks staged to haul it away the same day.

City records back that scale. In operations focused on RV and vehicle-dwelling encampments from May 2022 through June 2024, Los Angeles removed 714 tons of solid waste and 18.8 tons of hazardous waste from public rights-of-way, according to the City Administrative Officer’s report on the citywide RV strategy.

Routine programs in chronic encampment areas add to the pile. The city’s Skid Row Cleaning Services program alone reported about 369 tons of trash collected (35,604 bags) in one operating period summarized in a Board of Public Works transmittal in 2022.

And remember the Ballona Wetlands cleanup: In January 2023, after encampments were removed, a one-day sweep at the Ballona Freshwater Marsh hauled away more than 19 tons of debris, including over 200 pounds of hazardous materials and numerous needles.

All of this comes at a steep cost to taxpayers, with millions poured into hauling away trash from encampments year after year. Yet what we found is that the city still doesn’t appear motivated to curb the root of the problem. Instead, Los Angeles remains stuck in a cycle of cleaning up after the fact — an endless churn of truckloads and tonnage that fails to keep pace with the debris piling up on its streets.

Bass—Street cleaning is MIA

Mayor Karen Bass has acknowledged the city’s mounting trash problem. At an Encino community Zoom meeting on public safety in early August, she noted the decline in basic services.

“I’m not sure if you guys noticed this, but we don’t really have street cleaning anymore,” Bass said. “L.A. is dirty and has a very interesting history of being dirty.”

Jill Mather and her crew are committed to cleaning up Los Angeles. Photo courtesy of Jill Mather.

She attributed the decline to systemic cuts and restructuring within the Department of Sanitation that eliminated programs never reinstated.

Complacency Takes Hold

That vacuum has bred something more dangerous: complacency. When people get used to stepping over trash, they begin to accept it as normal. Researchers call this the “broken windows” effect — visible neglect signals that no one is watching, encouraging more of the same. Over time, civic pride erodes, fewer residents speak up, and the mess multiplies.

In Los Angeles, that means litter-choked sidewalks and trash-filled medians fade into the background. The danger is not just aesthetic — it’s cultural. Once people believe “this is just how the city is,” it lowers expectations for both residents and government, making the cycle of dirt and disorder even harder to break.

The stakes are bigger than appearances

The impact of litter is more than cosmetic.

When it rains, trash slides from freeways into storm drains, then into Ballona Creek and the Santa Monica Bay. The county’s trash interceptor in Ballona Creek has collected more than 125 tons of debris since late 2022.

At the coast, Santa Monica Pier again this summer landed on Heal the Bay’s annual list of California’s most polluted beaches, dragged down by bacteria carried through runoff.

Regulators are watching closely: in 2024, the Regional Water Quality Control Board instituted expedited penalties for municipal stormwater violations. Translation: missed cleanup targets can now mean faster fines — and again, all at the cost of taxpayers.

Caltrans says it’s committed

Caltrans, which maintains the state highway system, says it is working on its part of the problem. “Caltrans is responsible for maintaining the state highway system and remains committed to working with local communities to transform and beautify their public spaces,” said Katy Macek, spokesperson for District 7, which covers Los Angeles and Ventura counties.

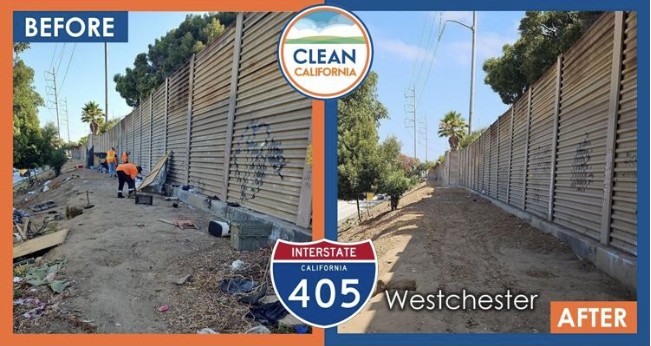

Macek pointed to Gov. Gavin Newsom’s $1.2 billion Clean California initiative, under which Caltrans and local partners have removed more than 3 million cubic yards of litter and debris from state highways since 2021.

In Los Angeles County alone, she said, crews cleared 48,000 cubic yards of litter in the last two fiscal years.

The department also touts education campaigns like its “Just One Piece” ads, and operates more than 300 beautification projects statewide, including new green space along Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard in Historic South-Central. Other efforts include a cleanup near Arbor Vitae Street in Westchester, and upgrades at Zela Davis Park in Hawthorne.

“Caltrans prioritizes cleanup efforts with its regular trash removal crews and special litter-collection stand-downs twice a month in all districts,” Macek said. “This provides additional crews to remove trash on our highways.”

Still, when we sent photos after the site cleanups, Caltrans didn’t have an answer for why the highways it maintains remain so dirty.

There are other massive players. The Los Angeles County Sanitation Districts, and the city’s LASAN, offer trash removal and myriad other services.

Bass said she has a new initiative that will focus on cleaning major corridors and restoring lost services. “One of my obsessions is trash. The city is dirty. And so we are getting ready to launch a whole concerted effort around that,” she said in the Encinco Zoom meeting, adding that despite tight budgets, it is still possible to restore basic services.

On the more grassroots level are groups like Mather’s CVV. In Los Angeles, 19 local organizations, from Pacoima Beautiful to the Rampart Village Neighborhood Council, have signed onto Clean California’s “Community Designation” pledge to demonstrate civic leadership.

The volunteers keep sweeping

Jill Mather and her crew are committed to cleaning up Los Angeles. Photo courtesy of Jill Mather.

Back in the Valley, Mather’s crew wraps the morning sweep and debriefs over coffee. Tomorrow they’ll be back on neighborhood streets, each person aiming for “never less than three huge 50-gallon bags.”

In the end, Mather says the fix starts with every Angeleno: “We need to stop people throwing trash. They need to be more accountable. They need to be more responsible,” she says. “Walk to the trash can. If the trash can’s full, then keep it with you and put it in your car and take it home.”

The rest, she adds, is neighbors showing up and calling in what they can’t haul themselves. She wants more people involved.

“More people have to stop deciding that it’s okay to throw trash,” Mather states. She notes that, even with all the billion-dollar slogans and stand-downs, the math doesn’t pencil out without civic muscle.

“We are not going to clean L.A. without volunteers. There are not enough funds. Volunteers have to clean it up.”

While trying to find my way home yesterday from a late dental appointment in Westwood, I was delighted to see an entire section of a freeway underpass on Sepulveda was sparkling clean. But only 3-4 blocks later while passing another freeway underpass, I discovered where all the tent dwellers and their trash went and the tent city was enormous! It is a game (or dance) the city and these street dwellers do. It is hopeless!! Unless the city imposes laws and only if it also enforces the laws it impose, I am afraid this city will remain dirty and trashy. Don’t we have anyone in the city hall of Los Angeles who has any pride and take responsibilities?!

People make trash. Millions of people make lots of trash and trash begets trash. Consumers generate trash. People who live on the street make stuff they need from trash and then recycle it back out into the streets. And we think throwing money at the trash will make it go away.

Please don’t be a litterbug.

In response to Mayor Bass “Um yes all of your constituents HAVE noticed you have not focused on a safe, clean, and trash & debris free LA. Put your plan in action instead of talking about it.”